This spectral texture of darkness, this melody in my bones, this breath from various silences, this going deeper and deeper, this dark, dark gallery... – Alejandra Pizarnik, "The Word for Desire", 1971 (translated by Yvette Siegert)*

Opening its first gallery in Düsseldorf in 2007 and its second in West Berlin in 2016 — occupying a dourly functional 1960s West Berlin office block which formerly housed the Czech Cultural Centre — the Julia Stoschek Foundation (JSF) has established a reputation for showcasing media arts, chiefly experimental video and film. And now it branches out.

After Images, a group show comprising more than 30 works by 18 different artists, is open until July 20, 2025. Curator Lisa Long, in her accompanying notes, positions the show as one answer to the question "How might we imagine what comes after images?"

Long's response is constructed via a sequential montage (a numbered progression through the various rooms) which she derives from cinematic theories propounded by Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov in the early days of Soviet revolutionary film. She cites Eisenstein on the Acropolis, which he dubbed "a perfect example of one of the most ancient films" because of the way visitors moved "between [a series of] carefully disposed phenomena that [he] absorbed sequentially with [his] visual sense."

After Images proposes a recalibration of our relationship to seeing and to contemporary image culture... the exhibition expands the visual realm to encompass the haptic and the multi-sensorial, and moves from the space of the screen to the embodied and experiential path of the visitor. The featured works put forward a wide definition of time-based art, including kinetic sculpture, sound and light installations, film-based installations, olfactory interventions, scores, and extended reality.

When assessing a show such as this, stated curatorial intention should of course be taken into account. The reality of After Images does not always match up to Long's stated ambitions — visual stimuli stubbornly predominates, even when paired with smelly emanations in Chaveli Sifre's camphor-exuding Adonia. But the exhibition's highlights collectively make for a worthwhile experience. And at just €5 for a ticket, which can be reused an unlimited number of times over the show's ten-month run, After Images is exceptional value. By comparison, the Nan Goldin retrospective at Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (open through April 2025) costs €16 for a single admission.

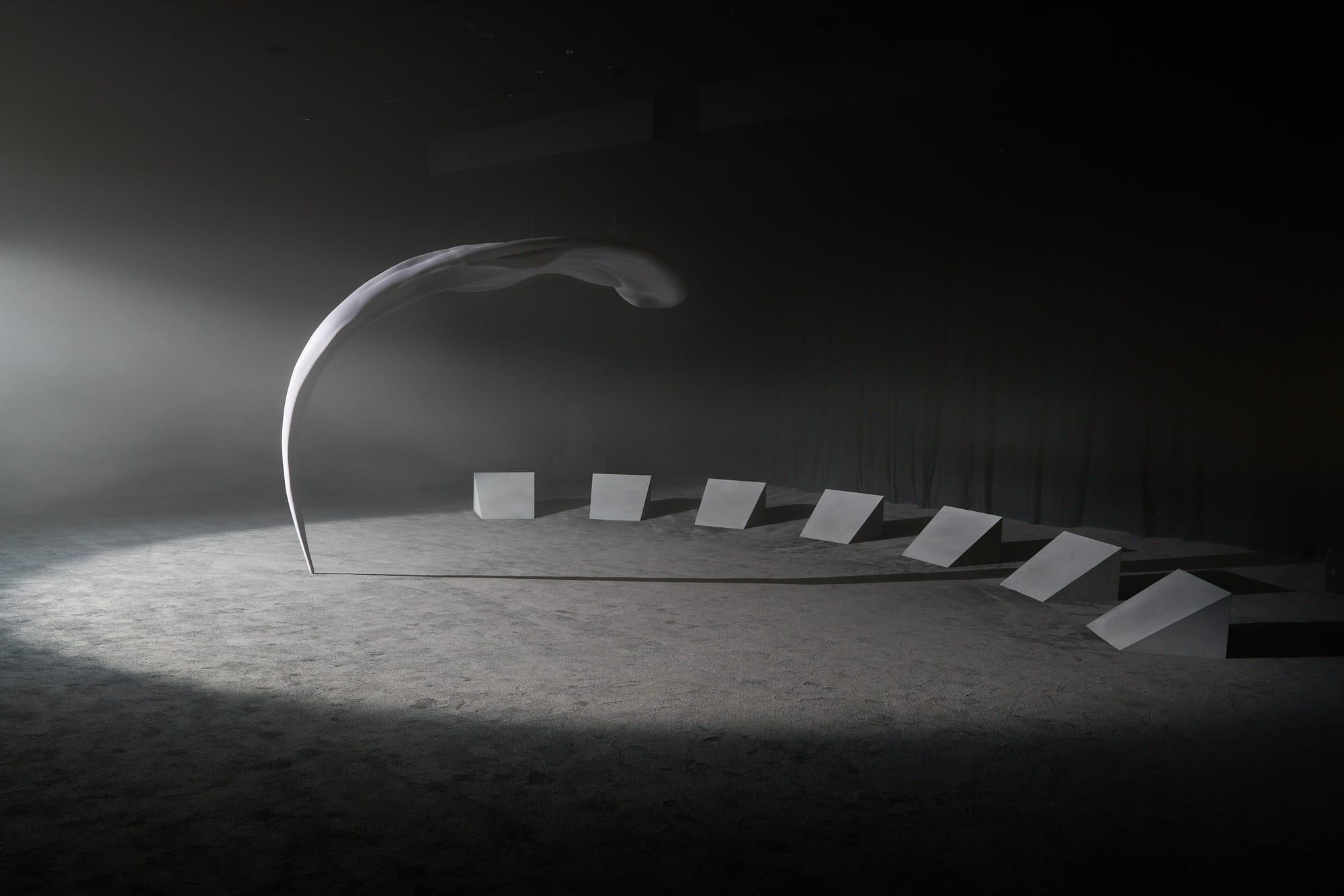

For the price of a caffe latte in a typical West Berlin business hotel, the After Images visitor can experience Tower of Silence, an intriguing new JSF commission from the duo LABOUR (Farahnaz Hatam and Colin Hacklander). It occupies the whole of a medium-sized room usually used as the gallery's cinema; the only seat available is a long, wide bench alongside one wall. Entry to the room is regulated according to the timings of a half-hour cycle (as indicated on a wall-mounted iPad); a bowl of plastic-wrapped earplugs is positioned at the entrance. A notice informs that the exhibit involves flashing lights and spells of low or no light. All of this stokes anticipation for some kind of full-scale sensory assault that will pummel ears and eyes alike, perhaps even nostrils.

What actually transpires proves at least a degree more restrained. We enter and observe a curved plastic sculpture around three metres high dominating the centre of the space, with a semicircle of what looks like audio speakers arranged around it. Tower of Silence, which according to the catalogue "references 3000-year-old Zoroastrian sky burials" is said to explore "three types of silence: forced silence, stoic silence and profound silence." Ironically, the noisier the audio input the more effective the experience: there are spells of rumbling intensity, in conjunction with strobe-flickering which gives the static curved thing a menacingly quasi-organic aspect.

Over 30 minutes Tower of Silence enables us to feel like we have strayed into the alien equivalent of a movie house, with pulsing lights (white, sometimes red) flooding the space from the projection booth's laterally-arranged windows. Towards the end of the cycle, dust flurries are illuminated by slanting beams, Anthony McCall style. The cumulative impression is of being bombarded via a "language" we have no hope of understanding, recalling the maddeningly impenetrable communications from extraterrestrial races in the literature of Stanisław Lem. And while the visual element once again predominates, the sonic dimension is here at least of equal importance.

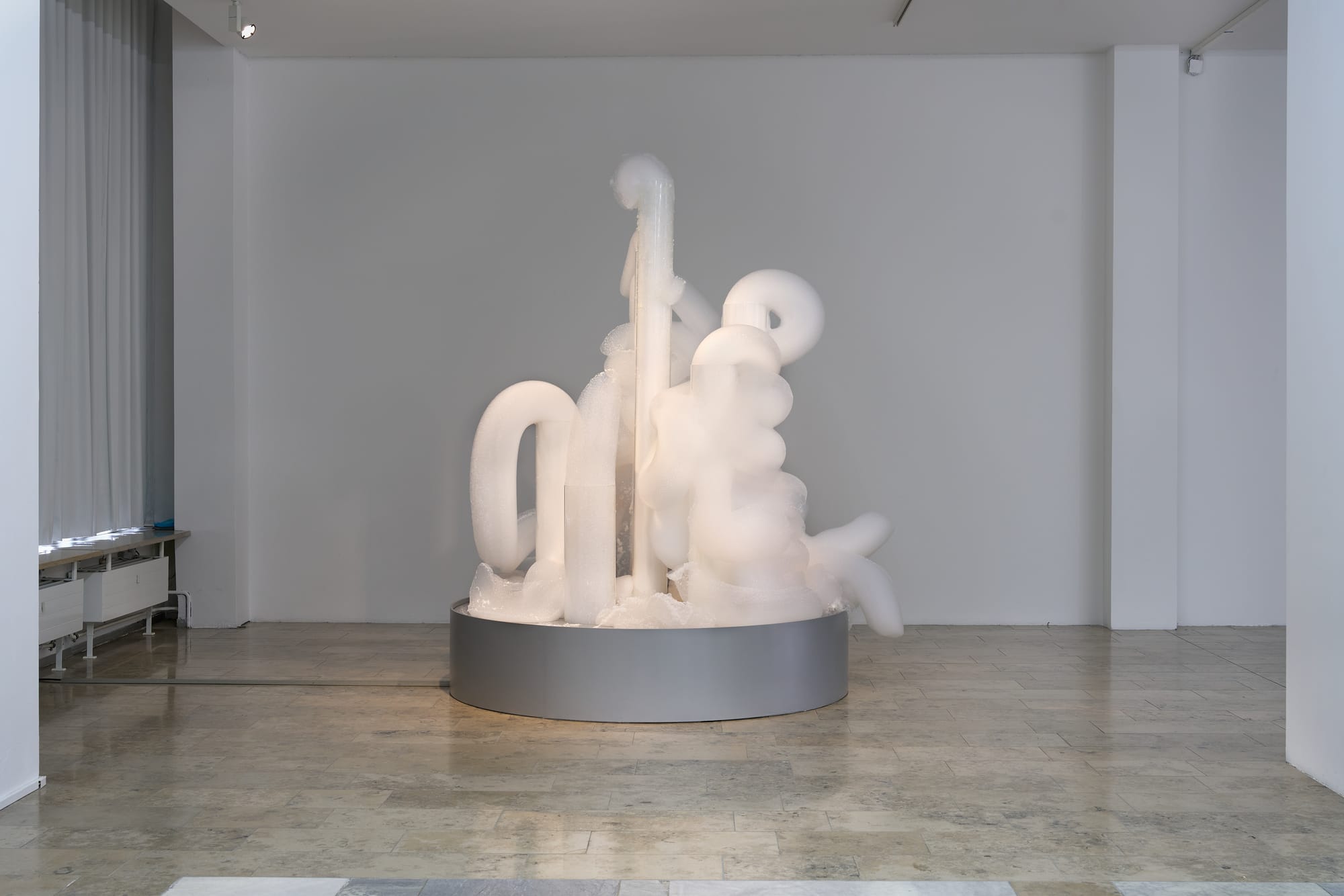

While Tower of Silence is a fascinating novelty, around a third of the works in After Images are on loan from other collections, including David Medalla's widely-exhibited bubble sculpture Cloud Canyons. First appearing in 1963, this is an elaborate system of vertical plastic tubes through which emerges a flow of soapy bubbles — these emit no particular odour or sound, and we are not invited to interact with them. Not an "image," of course, but nevertheless operating fully within the visual mode.

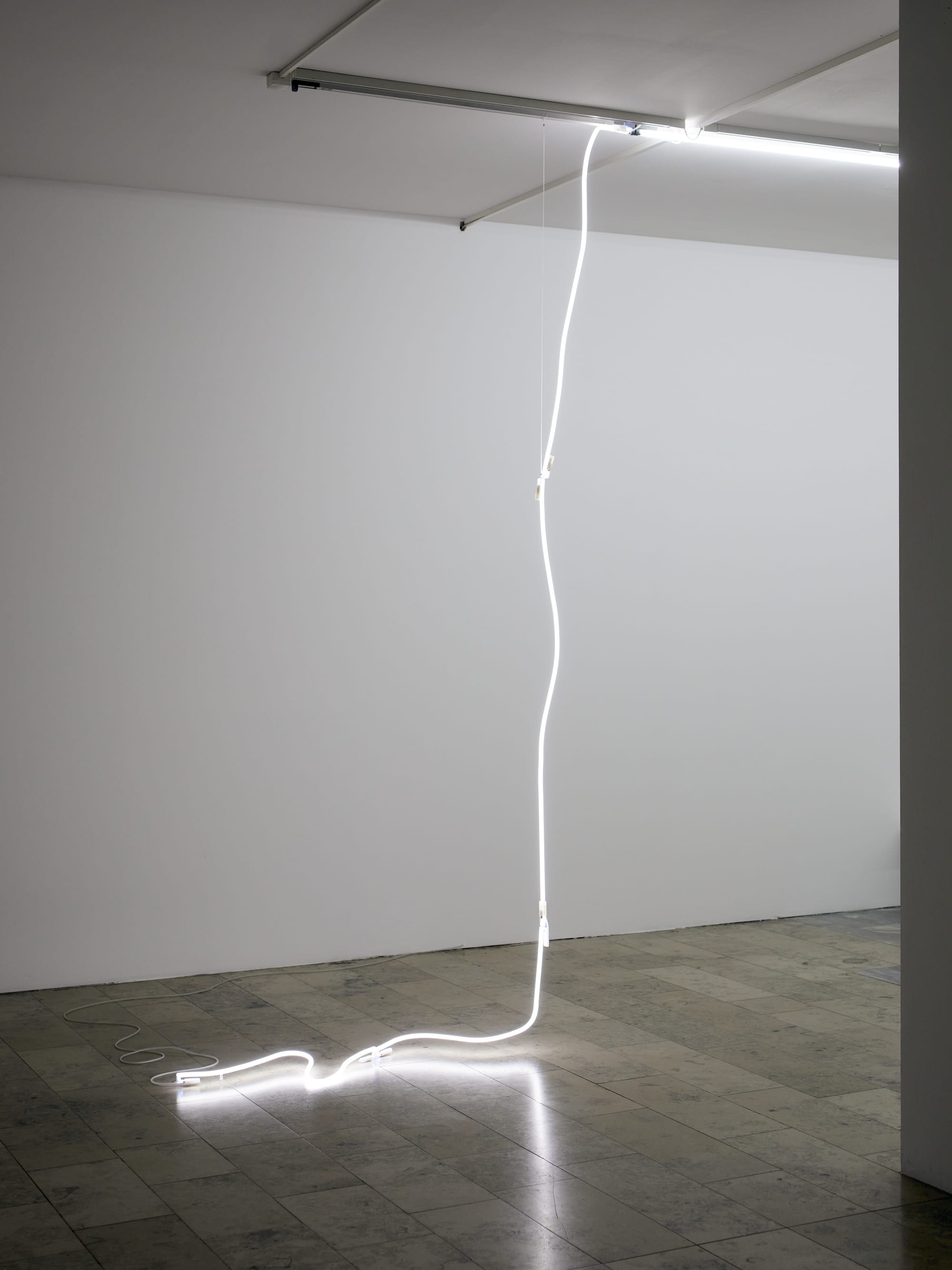

Rosa Barba's One Way Out (2009) is another loan on display. Barba, whose work has been regularly screened at film festivals, is represented by the most squarely cinematic element of After Images: One Way Out actually involves a 16mm celluloid strip running through a projector, the resulting image being beamed onto the lower portion of a gallery wall. The film is an undeveloped blank, but over the course of the exhibition slowly degrades by being run through an elaborate metallic piping system suspended overhead. The piece is best appreciated by means of regular visits, and thus adds something different to the category of "time-based" art with which JSF is usually associated.

The rest of the show, however, comprises works whose impact can be fully absorbed on a single visit. Some "speak" for themselves, others depend on elucidation from Long's catalogue — such as Theresa Baumgartner's "sight-specific light interventions." Located in seemingly innocuous corridors on each floor of the two-storey exhibition, The Breaking and If I Must Die, You Must Live to Tell My Story (...) consist of the gallery's overhead strip lights flickering on and off.

This intermittent light spells out in Morse code two poems, one by Swedish climate-scholar Andreas Malm, the other by the Palestinian writer Refaat Alareer (the latter text achieved widespread renown in the wake of Alareer's death during Israel's apocalyptic assault on Gaza.) Such an esoteric approach to the delivery of crucial information can of course be appreciated and admired on a conceptual level. But as the geopolitical (and indeed geo-climatic) situation continues to exponentially worsen, such techniques can increasingly seem obscurantist and thus counter-productive.

A more bluntly direct, but much more successful approach is taken by well-established musician/artist Carsten Nicolai's telefunken anti, comprising two flat screen monitors affixed to a gallery wall in an otherwise dark space. The artistic intervention here is that the screens are positioned the wrong way around, restricting the reach of their lights to a peripheral glow illuminating a few centimetres of wall space.

The on-screen content is derived from the audio signal of a CD player, plugged into the video sockets of the monitors and (per the catalogue) apparently comprises "an abstract composition of horizontal stripes," invisible to the visitor. Even the title of telefunken anti speaks unambiguously of the need to reduce our exposure to small-screen images, with both TV screens and computer monitors now hazardously flooded with propaganda, fake news and AI slop.

In this context it seems decidedly ironic that the show's standout component should be the one which most closely adheres to JSF-style video art, namely the small handful of contributions by Californian artist Trisha Donnelly. Donnelly (b. 1974) admirably refuses to play the art world "game." As Long puts it, "Her exhibitions do not come with explanatory press releases, her catalogues tend to dispense with essays, and she has limited the photographic documentation of her work... Her (refusals)... strike a prescient note against the tendency for over-interpretation, and the insatiable desire for image consumption."

Donnelly's work is immediately accessible on an aesthetic level: it is easy on the eye, alluring, enticing, enigmatic, hypnotic. On entering the first floor's largest room, we are drawn to a monitor displaying a six-minute video loop. This is Untitled from 2008 (all of Donnelly's works are so named), and presents a mirrored image of something pink: liquid, gushy, sensual, in constant flux. The mirroring effect, with streaky lines of of dirty brown-yellow down the middle like scratches on celluloid, results in something like a cross between a brain and a vulva, or perhaps the mutant Third Stage Guild Navigator from David Lynch's Dune (1984) given a Barbie-esque spin by John Waters.

Another, smaller ground floor room is given over to a 2012 Untitled, Donnelly's wall-projected video image of some kind of glassy-plastic blob on some kind of building's external surfaces, next to some kind of window (perhaps). The loop runs 3 minutes 59 seconds, at the end of which the image unexpectedly and briefly flares into a spray of yellow-red blurs before the original shot instantly reappears. All the while the room is filled with sound: a newly-commissioned 15-minute looped piece by American electronic music composer Laurel Halo titled The Word for Desire. This is an ominously orgasmic rush of organic and electronic sounds whose intensity counterpoints Donnelly's largely static visual component.

Halo borrowed the title from Argentine writer Alejandra Pizarnik (1936-1972), a prose poem which concludes with the violent, enigmatic sentiment "solitude would be this torn melody of my phrases". Long highlights this particular line in the After Images catalogue, confirming the ill-fated Pizarnik as a kind of secular patron saint of this show. Pizarnik, who committed suicide at 36, herself trained as a painter and was particularly influenced by the Surrealists before leaving such work behind in favour of literature. Perhaps she, too, wondered "how might we imagine what comes after images..."