“To be reincarnated in a stone or a speck of dust — my soul weeps with this yearning." — Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

Whether by accident or design, the most effective element of the Anthony McCall exhibition Rooms at the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) in the Belém neighbourhood of Lisbon is its specific physical context. To discover the subterranean space where it is installed, patrons (general entrance €11.00) must first pass through a much bigger gallery hosting Disco, a display of 500 riotously energetic paintings by Swiss-Argentinian Vivian Suter, likewise curated by MAAT deputy director Sérgio Mah (both shows run from October 30, 2024 to March 17, 2025).

Access to McCall's Rooms is via a discreet entrance in a side-wall; after turning three corners you enter a decidedly dark, minimalist environment of spectral calm in which four of the British artist's "solid light" pieces are displayed. The contrast is total, and instantly immersive: it is like stepping from a busy Lisbon street into the hushed calm of a dimly-lit church.

The fifth element of the McCall exhibition is a framed photograph — Room with Altered Window — positioned near the threshold of the exhibition's enticingly stygian main section. It shows the origin of McCall's distinctive praxis in 1973, when (as Mah puts it in his introduction to the exhibition) "he covered the window of his studio with black paper with a narrow slit cut into it. When the sun shone through the window, this caused a flat sheet of light to be projected into the room, rendered tangible by the dust in the air and cigarette smoke."

From 1973 until 1979 — a period when McCall was a member of the London Film-makers Co-operative, alongside Malcolm Le Grice, Peter Gidal, Sally Potter and John Smith — and again from 2003 onwards, he sought to reproduce and emulate this effect, initially via analogue means and later digitally.

The show at MAAT — an eye-catchingly futuristic white meringue-like swoosh of a building on the Tagus quayside, designed by London firm AL_A, and which opened in 2016 — includes four such works: Rooms (2020), Split Second Mirror I (2018), You and I Horizontal II (2007) and Skylight (2020), each replaying simple digital projections in cycles of 21, 16, 30 and 16 minutes respectively. Each relies for its effect on the discreet presence nearby of a "haze machine," a squat oblong box which, in the gloom of the exhibition, some may mistake for a seat — on closer inspection, a pair of wooden slats along the top of each box disinvites such usage.

In the 2020-vintage Rooms and Skylight the projector is located above a plinth, casting its beam vertically downwards. These simple works are variations on the same theme, the lines of light slowly moving but retaining an essentially cone-like effect which recalls McCall's international breakthrough from 1973, the 30-minute avant-garde film Line Describing a Cone.

Both Rooms and Skylight feature soundtracks by David Grubbs: an unobtrusive hum for Rooms, a more spectacular evocation of rain and thunder for Skylight, with a single pulse of lightning once every couple of minutes. This is the closest the exhibition comes to having anything resembling a narrative element.

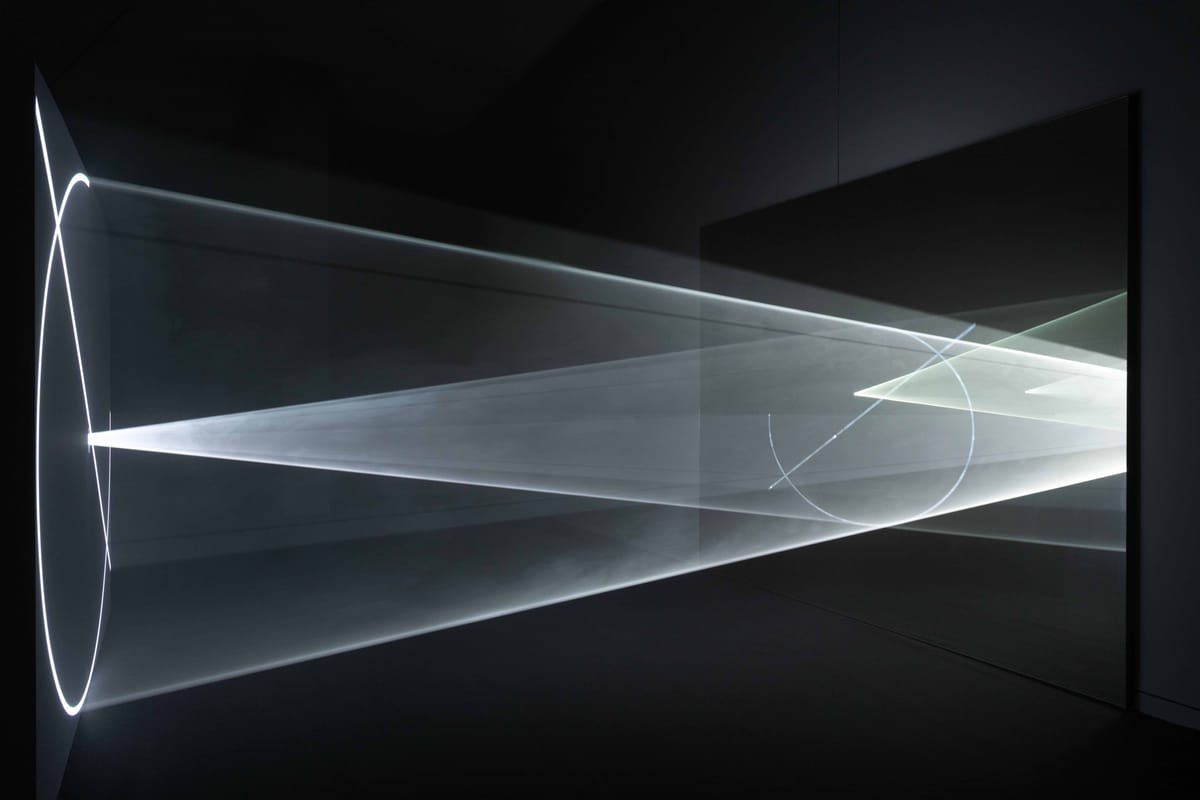

Playing in silence but bigger in scale, more interactive, and more spectacular in visual terms are the two pieces which involve horizontal projection: Split Second Mirror I features a large wall-mounted mirror which bounces back the projected lines and curves onto an opposing wall, in front of which the projector itself is located. The spectator can observe this from the outside or enter the space and become part of the exhibit themselves, the outline of their body blocking and shaping the resulting beams of light.

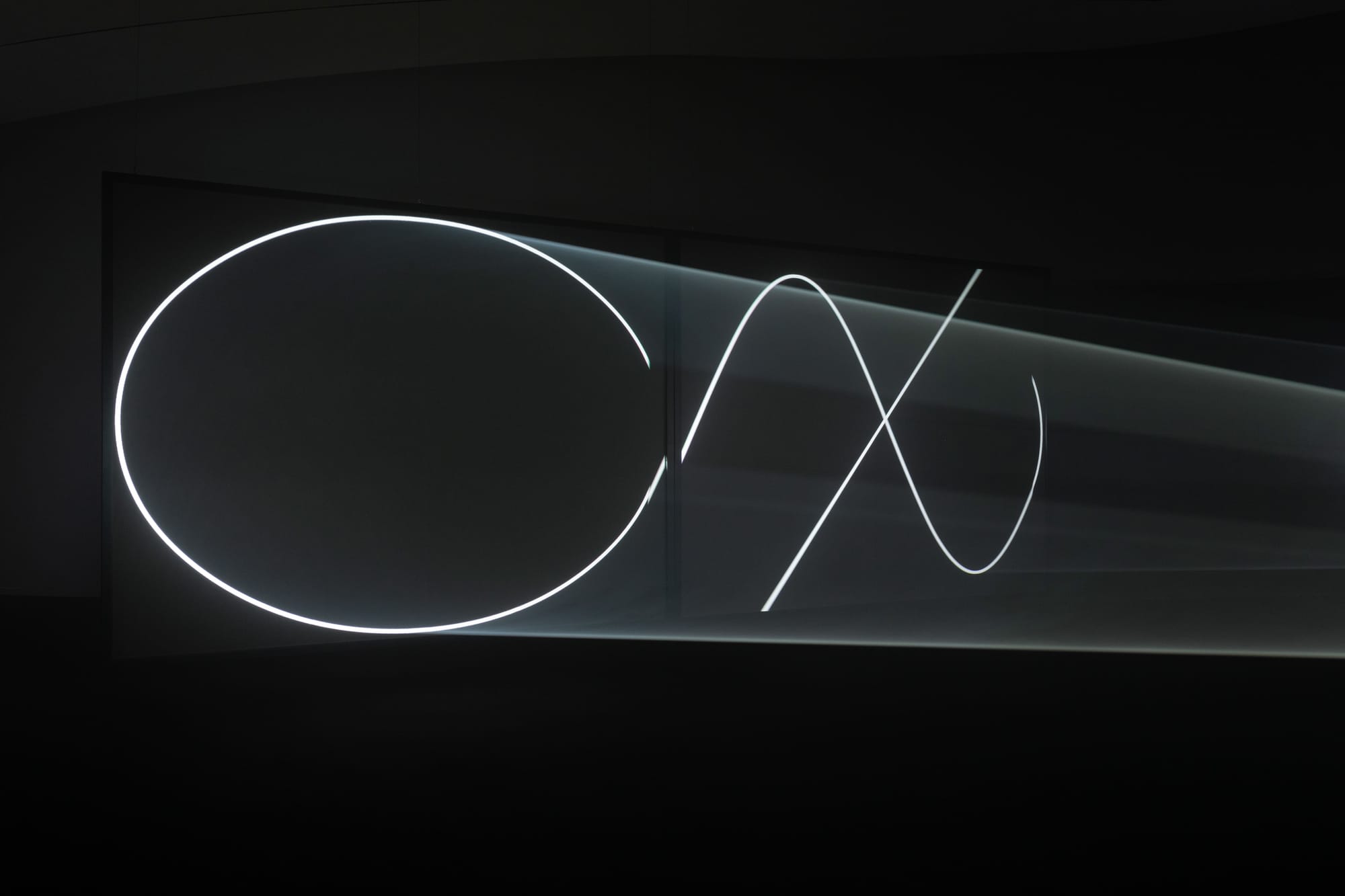

You and I Horizontal II involves two projectors casting their beams, separately, onto a wall about fifteen paces away. Here the maximum effect is achieved by positioning oneself against the wall, staring down the light-beams towards the projector itself. The piece is thus cinema in neat, perhaps even perfect reverse. The lines and curves gradually change over the course of the cycle: sometimes tunnel-like ellipses, sometimes more of an angular X-shaped intersection.

Standing against the wall and contemplating dust while staring at a clouded bright light at the end of such a "tunnel" makes it almost impossible to avoid reflections on mortality and the mind's eventual physical experience of dying. The Rooms exhibition can, for those so imaginatively inclined, take on the feel of a liminal space between existence and whatever (if anything) comes next.

In the case of both horizontally-projected works, the greater the interaction by the public the more effective the result. The haze machines create a steady flow of microscopic dust particles, which can be augmented by the simple expedient of scuffing one's shoes on the black fabric carpets underfoot. After a few seconds, this sends up small clouds of dust into the thin projected beams, yielding rippling, evanescent eddies.

The effect is even more dramatic if one rubs bare skin, presumably due to the warmth of the microscopic flakes and dermal particles which are released into the air. In each of the four main Rooms pieces, McCall reveals just how much quasi-invisible dust there is all around us at nearly all times, and how we continually subtly alter the space around us by our movements and breathing. The interactivity which they invite turns the visitor into a participant and even a kind of artistic collaborator; we can also discreetly (and rewardingly) observe how others sharing the McCall-modified environments behave (no one else seemed to have discovered the scuffed-shoe-shuffle trick).

The hour or so I spent inside Rooms involved periods when I was alone, times when I was with a small handful of others, and a stretch of 15-20 minutes when a dozen or so youths (presumably there on some kind of educational visit) effectively took over the place in agreeably boisterous fashion. "Imagine being here on, like, shrooms!" laughed one of this group, experiencing the trippy trompe-l'œil of a light-tunnel.

While the experience would indeed be heightened by the consumption of hallucinogens, prolonged exposure to Rooms itself enables access to an agreeably altered state. Passing back through Suter's Disco and then out into the unclouded sunshine of a January afternoon, my eyes re-adapted rather more rapidly than my brain.

It is surprising to note that Rooms is the first solo exhibition by McCall to take place in Portugal, given the fact that his artistic career spans more than half a century (albeit not a full one, taking into account the hiatus in the 1980s and 1990s.) Indeed, the lo-fi sci-fi ambience of his spaces straddles and eludes conventional chronological categorisation: it is simultaneously futuristic and bygone, the interaction of haze and light now pungently redolent of 1970s prog-rock concerts or 1980s New Romantic nightspots.

Does McCall’s art “speak to” 2025 in any meaningful sense? Does it need to? The simplicity of his engagement with uncomplicated technology instead places it in a parallel time-space altogether, a tenebrous kind of twilight-zone into which we are politely invited to temporarily segue.