Kevin B. Lee is an accomplished video essayist, professor and a pioneer of desktop cinema. He grew up in San Francisco a young cinephile who dreamed of being a director but found himself a working film critic as an adult. Coming of age with accessible digital tools and social media, he began practicing a videographic film criticism, becoming known for his prodigious and innovative output and quickly gaining a large following on Twitter.

Lee decided to pursue his graduate studies as an artist at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, finishing in 2015. His thesis film, Transformers: The Premake, will go down in history as one of the most influential student works of all time. With it, the desktop documentary was introduced to the world. Lee then embarked on his second career as an educator and an artist.

In 2016 he was given his first major solo exhibition at Austrian Filmmuseum in Vienna. In 2017 he was the inaugural Artist in Residence at the newly-established Harun Farocki Institut in Berlin. In 2022 Lee was appointed to the position of Professor of the Future of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts at Università della Svizzera Italiana in Lugano, in partnership with Locarno Film Festival. He is currently organizing his first major project at the festival, the conference Cinema Futures, opening in August 2024. Participants include Hito Steyerl, Laura Huertas Millán, Suneil Sanzgiri, Christopher Harris and other artists and academics.

We interviewed Lee about the practice of video essays, the afterlives of cinema and the trajectory of his career. With additional editing by Konstanze Winter.

Let’s start with your past. You did your graduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. What was the environment like at SAIC at that time?

For me, SAIC was the perfect environment. I had been a freelance film critic and video essayist for several years, spending up to 12 or 15 hours a day in front of my computer watching movies, writing about them, making video essays, and posting on social media. It was both financially unsustainable and existentially exhausting. I went to SAIC because I saw film professors using my video essays to teach their classes. I thought, if they could make a living using my work, then surely I could too. I just needed to get a Master’s degree to qualify for teaching, and that was my main motivation for going to SAIC.

But what I didn't expect was how creatively energizing it would be. SAIC is at the intersection of film, art, and all these other creative fields like 3D design, new media, and photography, with people from all over the world pursuing their visions. It was mind-blowing. I'd walk into the main campus building on McLean and immediately feel this buzzing energy. It was a game changer for me. I was the oldest student in my cohort by at least five or ten years, so I came into it a bit late, but I had a clear purpose and mission. After struggling in the freelance world for so long, I was just so grateful to be in that space and wanted to take advantage of every moment.

This is the ten-year anniversary of your signature work Transformers: The Premake. How did that video tap the zeitgeist, and how did it change your life?

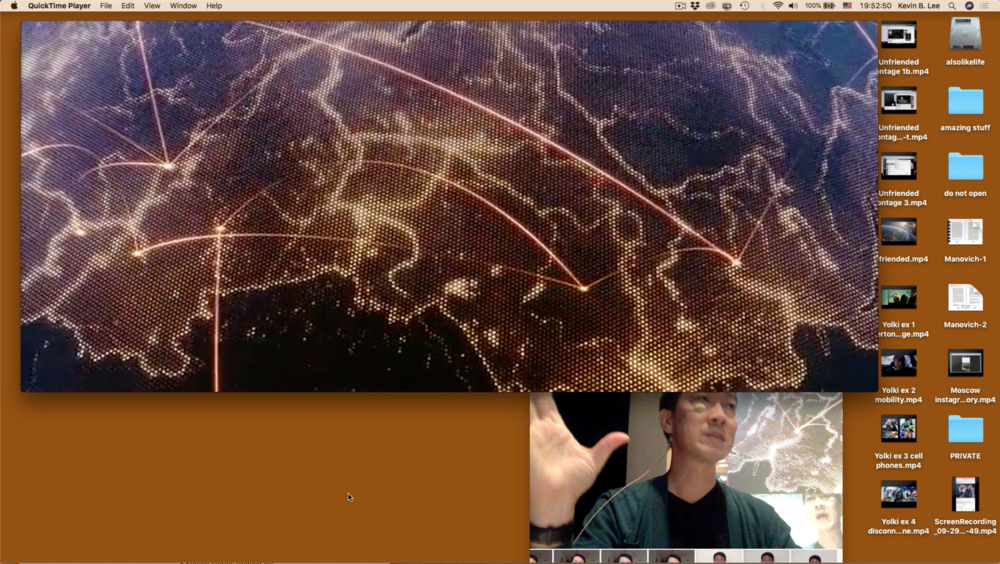

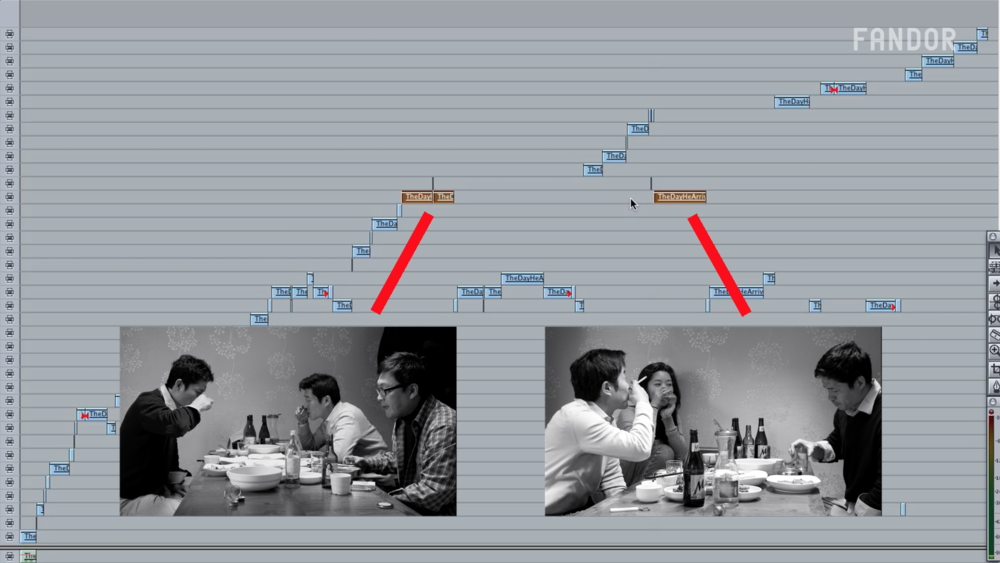

I don't know if it tapped the zeitgeist, but it definitely tapped into my own as a digital media laborer spending so much time online and wanting to get away from my desktop. It gave me a fresh perspective. I wanted to make a documentary about movie-making, to take my video essay practice into a physical space. That was my initial idea for the Transformers project. But after collecting footage and seeing hundreds of people filming on the Transformers sets worldwide and posting their videos on YouTube, I realized the film actually took place in a virtual space. It brought me back to my desktop to understand how social media and personal devices were creating a new kind of cinema experience — more interactive and creating new relationships between social media and cinema, and raising new questions about film production, promotion, and spectatorship.

It naturally developed into a desktop documentary. I didn't plan it that way, but it resonated with people in media studies, cinema, and especially my friends who spent a lot of time online. They saw a story that took place in a world they knew. It opened me up to new possibilities for making video essays and cinema, showing that sometimes what you're trying to get away from is actually what you're meant to do.

Courtesy of the artist.

What is desktop cinema? Is it a genre, or sub-genre or something else? Is it a practice or a modality?

I guess it would be a genre if enough people were deliberately seeking out desktop films, like how people used to go to the horror or romance sections of a video store. Genre is a mode of consumption — it's about the type of product you're interested in. But I don't think desktop cinema has that potential. However, I am reminded of how Lauren Berlant used to describe genre, as a set of strategies for making sense of life experiences. Horror, romance, comedy, and action are not just film modes but modes of life experience. In those terms, desktop cinema makes a lot of sense as a mode of understanding the world, and that’s what’s crucial about it: desktop cinema allows us to understand how the desktop is a mode of making sense of life.

It's interesting because, aside from experimental films, desktop cinema seems to lend itself more to horror. The most successful desktop film, Unfriended, is a horror movie. So, why does desktop cinema fit horror so well? I think it reveals the underlying anxiety of living on the internet — a space that feels like it's yours to control and manage but is actually vulnerable to infiltration, surveillance, glitches, failures, and hijacking. It’s a space of abjection.

After making Transformers: The Premake, I resisted making more desktop films because I didn't want to be labeled as the guy who makes desktop documentaries. In retrospect, I regret not leaning into it more, as it offers a lot of room for exploration. It's just a matter of coming up with ideas to push it further. My current film, Afterlives, is a multi-year project I've been working on since 2016. It deals with online media violence and trauma, and it took time to develop different ways of representing those experiences on screen.

Desktop cinema made me think carefully about what type of experience to explore and how to represent those experiences. The desktop is a very personal space, so seeing someone else's desktop feels privileged and voyeuristic, creating excitement, intensity, anxiety, and empathy. When the desktop feels compromised or something goes wrong, the feeling of dread increases because it starts to feel like it’s happening to your own space. That vulnerability becomes contagious, highlighting the nervous energy built into the desktop environment.

You previously taught at Merz Academie in Stuttgart. A few years ago you began your current position as Locarno Film Festival Professor for the Future of Cinema and the Audiovisual Arts at Università Svizzera Italiana in Lugano. What style or approach defines you as an educator?

Definitely openness and experimentation are key. It goes back to when I had to make a video essay each week for websites just to barely afford a living. I had to work quickly and efficiently while engaging with multiple films, and turning that engagement into a video essay. It was about being actively interested in something and asking myself what stands out to me as I watched a film. Noticing and being sensitive to my experiences, then using those insights to create prompts or materials for my expression. How can I give form to those experiences?

This approach relates to Jacques Rancière’s ideas in "The Ignorant Schoolmaster" and "The Emancipated Spectator". "The Ignorant Schoolmaster" starts from a position of knowing nothing. By not making assumptions or bringing any predetermined knowledge to the experience, it fully allows for the experience of discovery. And with "The Emancipated Spectator", you're viewing in a state of freedom. Freedom to discover and notice whatever comes to you, and that actually becomes part of your own language. What you observe is actually becoming something of a statement, like your eyes are speaking both to you and then through you. That's how I practice my work as an educator and video essayist. It’s giving spectatorship a voice.

At Merz Akademie I emphasized the concept of the 3 C’s of crossmedia: Critique, Create, and Communicate. First, notice what interests or questions arise, then use that as the basis for creative expression. While creating, think about how it connects and who it speaks to. Unfortunately this connection is often missing in arts education, where the hothouse environment for creativity often lacks dialogue with a real world context. It's crucial because education, creativity, and art are ultimately social projects.

In August this year you are organizing a major public program at Locarno Film Festival with the title Cinema Futures. Can you speak about your plans for this summit, and particularly about the theme Cinematic Survival?

This is a new initiative that aims to bring the best of academic and scholarly research to film festivals and cinema. We're inviting leading film scholars for three days of discussions about cinema's future, focusing on digital transformation, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability.

In our preliminary discussions about the question of what is the future of cinema, the word "survival" kept coming up. With thoughts about the future of digital technology, AI feels as much of a threat as an opportunity, affecting labor and how images determine our understanding of the world and society. There is so much instability happening now with the rise of autocracy, threats to democracy, major ongoing wars, and it is pretty well established now that the climate crisis is only intensifying. So, survival became a key theme for the conference.

We'll have great talks by Paul Trillo, who is one of the leading AI filmmakers, Suneil Sanzgiri, who has used an array of digital media practices to explore themes of migration and diaspora, and Susan Schuppli, who is an artist working along the lines of environmental justice. I'm especially excited that we'll use video essays and audiovisual techniques to express the ideas we encounter. This aligns with the approach I was talking about before, which is combining critique with creative expression. This conference will merge theory with practice, connecting really amazing ideas with a form that can hopefully reach a wider audience at the Locarno Film Festival and beyond.

In 1895, Louis Lumière famously stated that cinema is an invention without a future. Jean-Luc Godard, somewhat infamously, codified it in 1967. How should we read that statement in 2024? What futures do you envision for your work, both as an artist and as a professor?

It's interesting that this sentiment of futility has been with cinema ever since the beginning. Maybe it has to do with the expectations that we have for cinema, because cinema has such tremendous potential that it's always perpetually failing. And so that leads people to pronounce its demise prematurely. We might be in such a time now with streaming entertainment, social media, AI and other audiovisual forms that seem to compete with cinema but might actually be helping cinema find its next life. That’s how I prefer to see it.

I've personally always had a hard time envisioning my future. I've wanted to make a feature film since I was a child. Circumstances led me to be a film critic and then a video essayist and a desktop documentarian. And now I am finally making my first feature film, which is called “Afterlives”. Hopefully it points to an afterlife for myself and for cinema.

The future is never what we expect and that’s what's beautiful about it. Cinema will stay alive as long as it defies our expectations.

Thank you!