Since Legacy Russell became Executive Director and Chief Curator at the storied arts institution The Kitchen in New York she has steadily built a program that is fluid, innovative and committed in its dedication to (re)defining the avant-garde for the 21st century. Russell crafted her reputation as an incisive arts writer and adventurous curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Her books Glitch Feminism and Black Meme are already key reference points for critical engagements with the internet, race and politics.

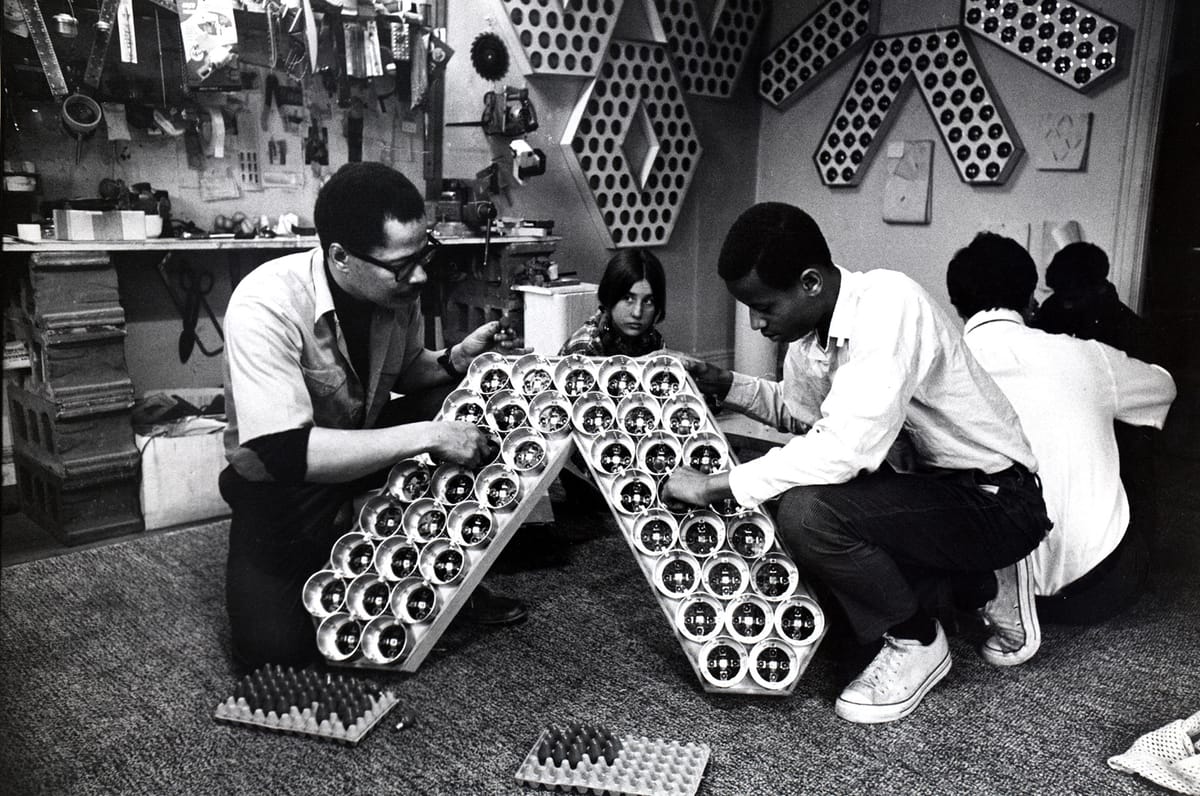

Because of this affinity for thinking with and through technology that she has displayed in her writing, it seemed inevitable that Russell would eventually organize a major exhibition that interrogates these intersecting fields. That show is now in the world. Code Switch: Distributing Blackness, Reprogramming Internet Art is currently on view at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. This pioneering exhibition explores and redefines the history of “Black data”, centering and celebrating contributions by artists of African descent to the rapidly advancing field of new media art and digital practice. Staged in two chapters, the second presentation will take place in Spring 2025 at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. We spoke with Russell about her process and the multiple historical and creative layers unfolding in this project.

This post is for subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.