Reviews

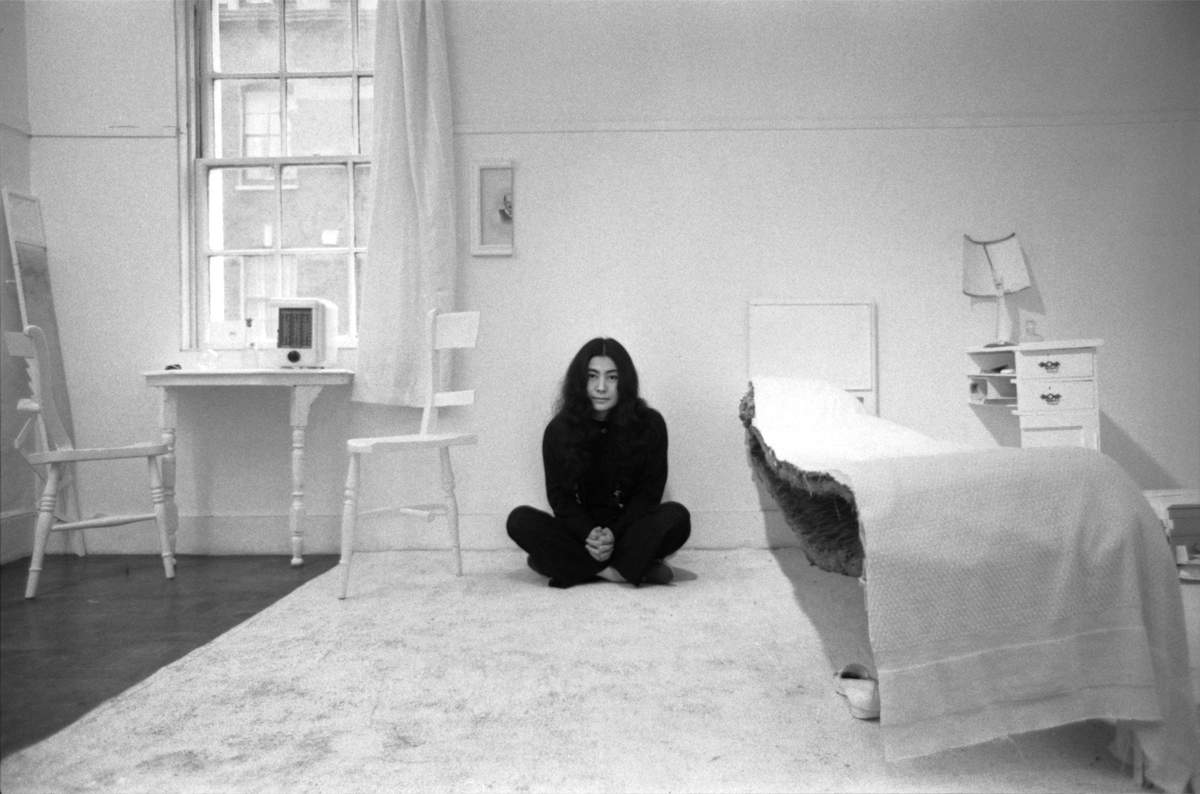

Yoko Ono, for all the adulation she has received in the multiple arenas of her career, might still be a bit underrated as a moving image artist. This becomes evident when viewing her solo exhibition Music of the Mind at Tate Modern in London, which is a broad retrospective that stretches from her early conceptual pieces of the 1950s to her installations and actions of the past few years.

This post is for subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.